Posts Tagged ‘bias’

Designing Systems to Limit the Impact of Bias

In March, we wrote about how coaches and evaluators must identify, then set aside, biases in order to fairly and accurately evaluate and develop teacher practice. This critical work by individuals is powerful, but not the only tool available to leaders and policy makers in reducing bias: Specific design elements within performance management systems can help reduce opportunities for bias to impact results.

Drawing upon findings from the MET Study and our practical experience with school systems across the country, we recommend three design features to limit biases:

- Balance with multiple measures: Evaluations that rely on a single input are not only more vulnerable to year-over-year volatility but they present the greatest opportunity for evaluator bias to impact outcomes. Consider, for example an evaluation system with one input, ratings on a common teaching rubric. As evaluators work to determine ratings, their biases can (and will) creep in. Without a second or third objective measure to balance the overall evaluation, the teacher’s rating is subject to the influence of these biases with no checks or balances.

- Utilize multiple observers/evaluators: As with multiple measures, adding additional observers/evaluators increases statistical reliability (reliability = overall consistency of a measure). MET Study authors write: “When the same administrator observes a second lesson, reliability increases from .51 to .58, but when the second lesson is observed by a different administrator from the same school, reliability increases more than twice as much,from .51 to .67.” While districts must wrestle with the best allocations of limited time and resources, there is great benefit to having a second set of eyes on a teacher’s performance.

- Use outcomes-based tools: Many common evaluation instruments measure inputs–the actions taken toward a goal–rather than assessing the desired outcomes. Unfortunately, measuring inputs can yield false positives: a teacher can try a specific approach and receive high marks, even if the strategy fails to produce appropriate student learning. Instead, strong evaluation systems use outcomes-based tools and rubrics that identify observable and measurable behaviors. For example, we’re big fans of the Core Teaching Rubric, which describes with specific language what students are saying and doing at different levels of performance–rather than teacher actions–so that observers can evaluate performance based on what matters most: student experience and learning. By focusing on student outcomes, there is less risk of observers inserting their biases or preferences for a particular instructional strategy. Instead, an outcome-based tool focuses observers on what and how students are learning, which is what matters the most.

While these structural changes alone will not eliminate bias, they can make a big difference. What have you seen be successful in reducing bias in performance management? Let us know in the comments!

Three Steps to Avoid Common Observation Biases

We all have biases. Whether picking an ice cream flavor or choosing to take the scenic route rather than the highway, we all operate with mental models that place disproportionate weight on certain factors that move our judgment in favor of one option when compared to another.

When observing and evaluating teacher practice, there are numerous opportunities for biases to creep in. Just think of all the factors that go into a lesson: the subject, grade, school, teacher, time of day, lesson structure, materials used and more. An observer may think to themselves, “the students were well-behaved for the first class right after lunch”. A different person observing that same lesson may think, “if I was teaching this class, I would have used a different text.” Both of these sentiments may be true, but they have to be placed aside before conducting a visit so that observers can focus on objective teacher and student actions.

In short, great observers, coaches, and evaluators must identify, then set aside, biases in order to fairly and accurately evaluate and develop teacher practice.

Common biases include:

- Confirmation bias: the tendency to search for or interpret information in a way that confirms one’s preconceptions,

- Halo effect: the tendency for a person’s positive or negative traits to “spill over” from one area of their personality to another in others’ perceptions of them, and

- Mirror bias: the tendency to judge performance as “good” if it is “like I would have done it.

A full table of common observer biases with examples can be found here: Observer Bias Examples

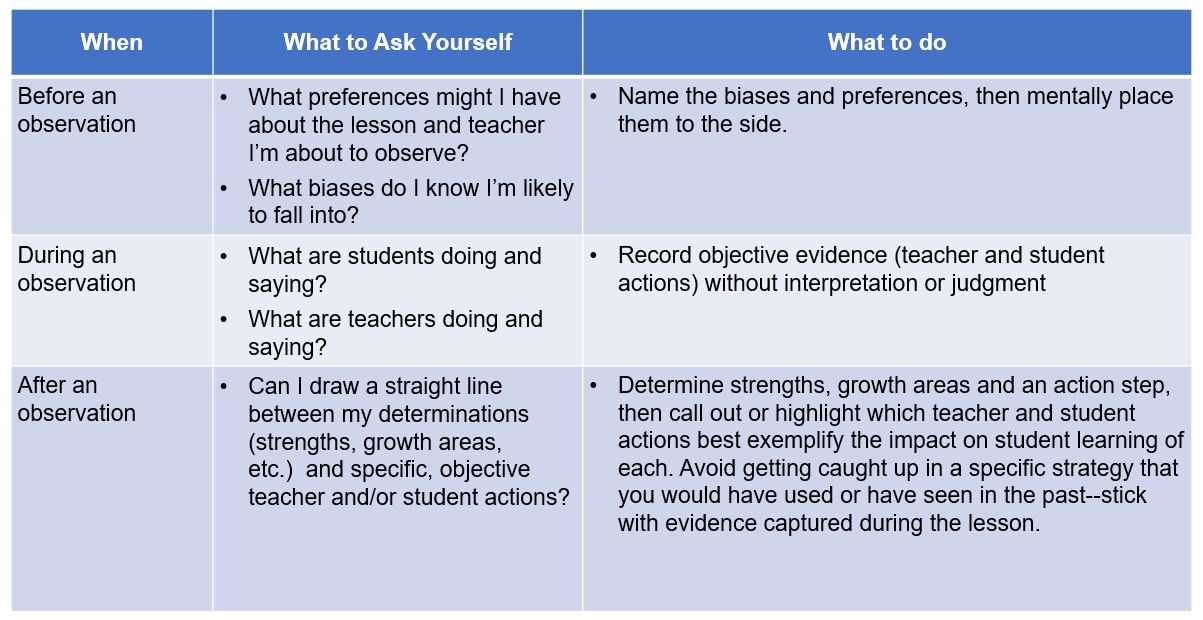

In order to mitigate the impact of these biases, great observers should ask themselves three questions: